Where Have All the Characters Gone?

by David Ellis

Autumn 1998

Characters epitomize the Chinese language: works of art to those who know them, ungainly squiggles to those who do not; pregnant with the accumulated meaning of millennia to those who understand them, inscrutable to those who do not.

I studied Cantonese at CLS in the early 70s, under the inscrutable eyes of Messrs. Tse, Li, Wu and Ho, and in the delightful company of just one classmate, the erudite eclectic Bill Guest. At the end of two years of first-rate and virtually private tutoring, Bill and I had conquered enough characters [by which, for literary purposes, I mean the language as a whole, not just 漢 字] to cruise through the Interpretership exams. A day or so before the exams, Mr. Tse had bestowed upon us his highest honour: the secret of his success at mahjong. It consisted of [1] finding some quiet spot, ten minutes to game time, [2] lying supine in said spot, and [3] emptying one’s mind of all thought. Guaranteed to produce razor-sharp responses and clarity of thought.

I don’t know about Bill, but I tried it before the Interpretership, on the floor of an unoccupied classroom, and it at least helped me avoid the celebrated but not very successful Brian Throssel-ian opening gambit of saying “Good-bye, gentlemen” in perfect Cantonese to a nonplussed examination panel.

Unfortunately, Mr. Tse’s technique was difficult to implement in the villages, streets, cabs and stores of Hong Kong, where the real test took place, as Bill and I were to discover when John Prince [then Commandant] threw us in at the deep end. The deep end was George Duckett, a delightful eccentric whose character John Le Carré would kill for. Outwardly straight about the mission, John Prince must have been in paroxysms of inner glee at our impending fate.

Major Duckett was a sort-of one-man Psy Ops unit created, I suspect, just for him, because the Army could not possibly have had any idea what else to do with him. He executed his task of winning the hearts and minds of New Territories villagers by giving each village a refurbished black-and-white TV set for the village hall.

Then he would tour the villages making sure the TV sets were doing their duty for Queen and Colony. George spoke neither Cantonese nor Hakka, the chief languages of the NT. He seemed to get by on the [astonishingly effective] British stentorian tradition, further amplified by exuberance. More likely, though, he got by through the unsung graces of the Chinese TV technicians who accompanied him and did the real work.

On the other hand, if there ever was an Army officer who would countenance a soldier’s request to take a short nap on the brink of battle, that officer was not George. He didn’t even give one time to ask questions; in fact, he asked the questions, which Bill and I were expected to interpret, along with the village headmen’s Canto-Hakka responses. Bill and I didn’t speak Hakka any more than George did, and truth to tell we barely spoke Cantonese. But we did at least know the Chinese for “TV set”.

Don’t laugh. At the mock Linguist exams about halfway through our stay at CLS, we had to interpret between a Chinese and a British general discussing a Sino-British joint exercise, Banana Boat. Try getting around that, if you don’t know the Chinese for ‘banana’ as I did not. “General Wu, General Smith proposes naming our joint exercise “Exercise Long, Yellow, Curved, Soft, Fruit Boat”. I’ll never forget the looks on Major Prince and Mr. Tse’s faces. When all the other characters have disappeared in memory’s mists these two: 香 蕉 shall burn brightly on.

Blessedly unaware of the Great Banana Slip, which might easily have precipitated a Sino-British incident had it been for real, George whisked us on a whistle-stop tour of villages in the NT. I’ll spare you [and me] the embarrassing details; suffice to say that we learned what I am sure was the real lesson John Prince wanted us to learn: that we were a long way from speaking real Chinese, at least without first internalizing three or four inspirational brown bottles of St. Michael’s elixir [San Miguel in green bottles, it was well established in Royal Hong Kong Police lore, was lethal].

More unfortunate still than the practical difficulty of implementing Mr. Tse’s mind-enhancing technique was the fact that it would have been a pointless exercise in the Yuen Long Police Station basement cell where I spent the subsequent two years in the company of an English typist and a Chinese…… translator. Talk about disincentive!

The only things that kept me from promptly losing every character I had learned at CLS were the ad hoc and largely liquid lunches with a wonderful group of non-English-speaking policemen at Lo Wu, and occasional trips to temples on behalf of the greatest god-hunter of all time, Keith Stevens [Mandarin, pre-CLS].

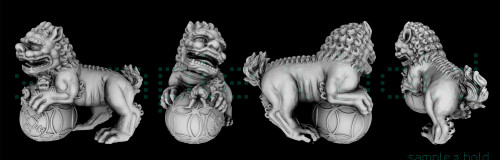

For half his life, Keith visited temples throughout East and Southeast Asia, talking to the temple-keepers about their gods, taking thousands of pictures of the altars and their assorted idols and occasionally purchasing a statue for his collection. The temple-keepers were probably less impressed with his Mandarin than with his grasp of China’s beliefs and pantheon. When I last met him [some 15 years ago], Keith had probably the finest collection of Chinese gods in the world – numbering some 600, if memory serves – housed in a specially built addition to his home. With the help of his wife, Nora, Keith had also written a manuscript documenting every single one of the thousand-plus gods he had discovered. It was a monumental, unique and priceless historical and cultural work, and I pray it has been or will be published, and that his collection of statues will eventually find a permanent home in some grand museum.

But I digress. The thing was, as a Mandarin speaker Keith was disadvantaged when it came to talking to the Cantonese, Hakka, and Chiu-Chou temple-keepers of Hong Kong, so he enlisted my help. I accompanied him as interpreter for a couple of trips, then he would send me off on my own to find obscure temples in remote reaches of the NT or even on the umpteenth storey of some Eastern District tenement skyscraper. I found a Chiu-Chou temple in one of the latter, and was entertained to Chiu-Chou tea – the genuine article: hyper-concentrated tannin stew served in dolls’ teacups – and to the temple-keeper’s version of Chinese philosophy regarding the death penalty, which Britain had recently abolished. We had done so, he said, because we knew that people were more afraid of imprisonment than of death. Abolishing the death penalty made us look humane in the eyes of the world, but we knew all along we were substituting for death a worse fate. He thought we were cunning devils.

I’m digressing again. The point is, after graduating from CLS I was barely able to hang on to the modicum of characters I had digested over two hard, if fun-filled, years. It didn’t get any better when I left the Army and my two year stint in the NT to work for the RHKP in its Wanchai HQ. Here I still had a team of translators passing on documents in Chinglish for me to edit into shape. For a total of nearly eight years I was surrounded by Cantonese people and their language, yet it took a career move to London to get me really immersed and back in the deep end. I worked with a Cantonese colleague [another Bill] whose English was worse than my Cantonese and I was required from time to time to meet with other non-English-speakers in the overseas Chinese community, without an interpreter. So I painfully regained some of my lost ground as far as the spoken language was concerned, though I lost more ground in the written language.

In Hong Kong one cannot avoid Chinese characters, but in London they are almost non-existent but for a sprinkling of neon signs in Soho’s Chinatown. Bill would bring in Chinese newspapers, but I gradually lost the ability to make much sense of them and eventually stopped trying. Since then I’ve lived in America for some 15 years, and my characters have gone right down the tubes, except for 香 蕉 and a few others. A couple of weeks ago, out of the blue came a call from a Michigan district court, which had somehow heard of my Interpretership, asking me to interpret in a case involving a non-English-speaking Cantonese. I had instant visions of “He says he didn’t kill him, your Honor. He says the man slipped on the skin of a long, yellow, curved, soft, fruit”, and promptly declined the invitation.

The CLS International Newsletter reminds us of all those other characters whose acquaintance we made at CLS; the human characters,. Through the Newsletter at least we know where those characters have gone. A great debt is therefore owed also to our illustrious [not to say elliptical – see his picture in the last Newsletter] editor, Mick Roberts, and his industrious and beautiful wife Kay.

* * *

The clearly-remembered bit of suffering up on the border with George Duckett and his merry men brought a big smile to my face. I was constantly looking for ways to add some realism (or more usually pseudo-realism) to students’ training and George was a gift from the gods. In my defence, if defence I need from David and Bill, I would point out that before they went, I too had spent several slightly bewildered evenings acting as interpreter between George and assorted village head-men.

Of course, before he got that job, CLS had been given a few months to teach him some Cantonese. All the staff were bemused by him to some degree, but my own ‘special’ memory of him was the moment when, in his second week as a student, he wandered into my office and said: “I say, John, I need your help.” This is always sweet music to a pedagog’s ears, so I asked what I could do. “Well,” he said “I’ve got Prince Michael coming for dinner tomorrow night and I’m a lady short. Need to borrow your wife, old boy, please!” They don’t make ’em like that any more.

Priceless.

Thanks, John, for the education.

David

Cherished memories of nights with George’s Army Information Team (New Territories).

I was just as baffled as John and David though when, still a fairly new student, David and I were faced with attempting to interpret from Hakka, a dialect then unknown to us – and not much better known now I’d guess.

Following that, the team would then perhaps fix the village generator and do any other odd jobs following which, much to the delight of the village kids at least, they would erect an outdoor screen and put on a film show.

And at the end of proceedings it would be off to the Better “Ole in Fanling for a beer – only the one in George’s case as he didn’t have a head for it – and home.

In addition to these outings George also regularly made weekend trips with his soccer team, made up of his HKMSC staff, to play against NT village sides, following which George would provide the winning team with large amounts of brandy, which he paid for himself, . Curiously however, the winners were almost always the village teams, who often won by many goals. It was only after a month or two of this that George’s bruised and weary players asked him if he was aware that wherever they played they would always find themselves playing a handful of the NT’s best players, who would surreptitiously move from village to village to play as ringers, and thus avail themselves of George’s largesse. He took it all with his usual good humour.

It was all terrific fun. Happy Days!

Ah yes. I had forgotten the Better Ole. Can you remember the name of the curry house we used to frequent? A Portuguese name I think. …

I think the curry house was Pereira’s. Wasn’t there a python slithering about the premises?

Rod Whitticase

Yes! A python! Not that I ever saw it (or if I did, I was too drunk to notice or remember), but that definitely rings a bell. Thanks, Rod.

David E.